TLDR

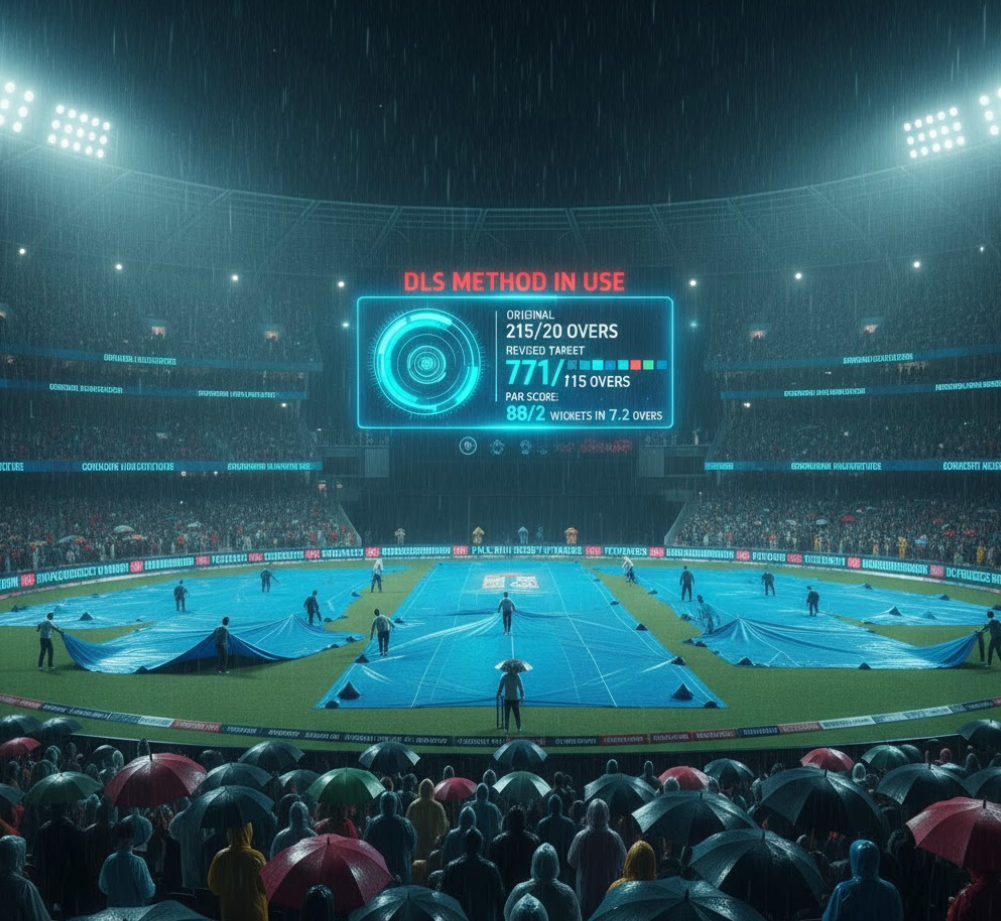

The Duckworth-Lewis-Stern (DLS) method is the officially adopted mathematical formula used by the ICC and, consequently, the Indian Premier League (IPL) to set a statistically fair target score for the team batting second in limited-overs matches that are interrupted by weather or other delays. The system works by analyzing the two key “resources” a team has—overs remaining and wickets in hand—and adjusts the target proportionally to the resources lost or gained by either team due to the interruption. The goal is to ensure the revised target maintains the same level of difficulty as the original target.

The Core Concept of DLS: Resources and Fairness

The Duckworth-Lewis-Stern (DLS) method serves as a critical mathematical formulation in cricket, specifically designed to address the challenges posed by interruptions, primarily rain, in One Day International (ODI) and T20 limited-overs matches. The core objective of DLS is to provide a definite result in limited-overs matches where bad weather might otherwise prevent a conclusion. It adjusts the target score for the chasing team (Team 2) to ensure the difficulty of achieving the revised target is statistically equivalent to achieving the original target.

Why Traditional Methods Failed (The 1992 Catalyst)

Before the DLS method, simpler, flawed systems were in use, which often produced absurd results. The most infamous example occurred during the 1992 World Cup semi-final between England and South Africa. South Africa needed just 22 runs off 13 balls to win when rain halted play. The revised target was calculated using the “Most Productive Overs” method, which shockingly resulted in South Africa needing 22 runs off just one ball—an impossible task. This absurdity, where 12 minutes of rain cost 12 balls or two overs, spurred English statisticians Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis to devise something better. Commentator Christopher Martin Jenkins voiced the general exasperation, noting that “surely someone somewhere could come up with something better,” which solidified the need for a mathematical solution. Had the D/L system been used then, South Africa’s target would likely have been reduced, leaving them four to tie or five to win off the last ball.

Understanding “Resources” (Overs and Wickets)

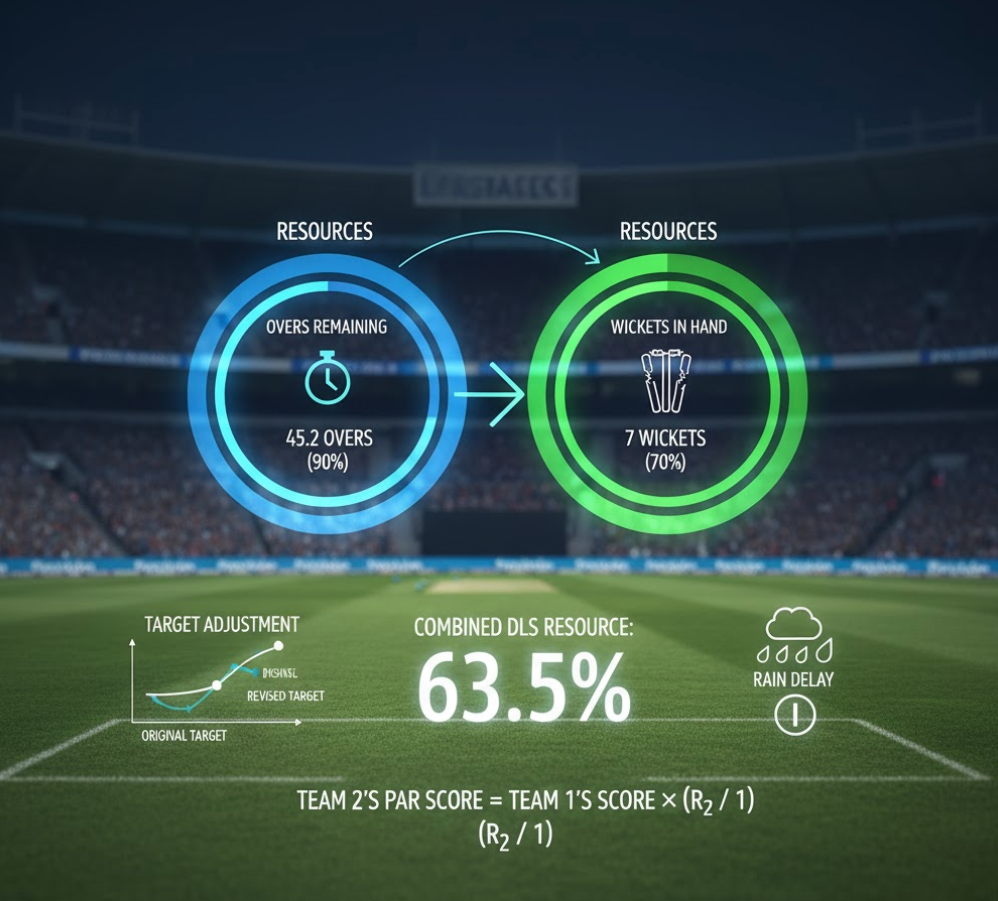

The foundation of the DLS method lies in the concept of “resources”. Every team in a limited-overs match has two resources available to score runs: overs remaining (or balls) and wickets remaining. The DLS system converts all possible combinations of overs left and wickets in hand into a quantifiable combined resource percentage. For instance, a team starting a 50-over innings with 10 wickets in hand has 100% of its resource available. A crucial insight of the DLS method is recognizing that losing overs is not simply a proportional reduction in required runs, because a team with fewer overs to bat (but all wickets intact) can afford to play more aggressively than one with a full quota of overs, thereby sustaining a higher run rate. The resource table quantifies how the combination of these two factors affects a team’s ability to score.

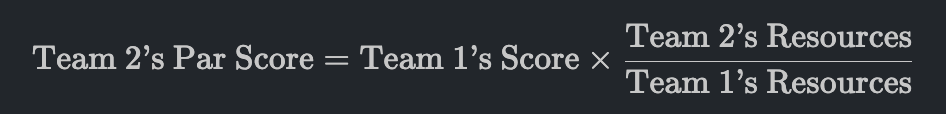

The Fundamental Par Score Formula

The DLS method calculates the target score, or the par score for the team batting second (Team 2) based on the resources available to both sides. The formula used in the Professional Edition (the version used in international and first-class matches like the IPL) adjusts Team 2’s par score in direct proportion to the teams’ resources.

The calculation is summarized as follows:

If the resulting par score is a non-integer, the target score needed for Team 2 to win is that number rounded up to the next integer, and the score to tie (the par score) is the number rounded down. If Team 2 scores less than the D/L Par Score when the match is abandoned, the bowling team (Team 1) is declared the winner; otherwise, the batting team wins. For example, if Team 1 scored 254 runs using 100% of resources (R1) and Team 2 only has 90% of resources (R2) available due to rain, the par score is 254 x (90%/100%) = 228.6. Team 2’s target to win is 229 runs, and 228 runs results in a tie.

DLS in the IPL and Limited-Overs Cricket

The DLS method has become the universally recognized standard for dealing with rain-affected matches in international cricket, and its use extends directly into major franchise leagues like the IPL. The system is mandatory because the IPL operates under the International Cricket Council’s (ICC) Playing Conditions.

The Official ICC Standard in International Leagues

The DLS method, in its updated Duckworth-Lewis-Stern form, is the official method adopted by the ICC for all international matches, including the World Cup and T20 Internationals. It replaced the original DL method, officially adopted by the ICC in 1999. The Professional Edition of DLS is specifically required for international matches according to the ICC Playing Handbook. Because the IPL is an Indian domestic tournament played under ICC Playing Conditions, the DLS method is the system used. The calculation is applied whenever a match is interrupted and subsequently resumed, or when the match must be abandoned, provided the minimum number of overs has been bowled.

Landmark IPL Match Decided by DLS

The DLS method has dramatically impacted critical moments in the IPL, including the championship match. A very recent and high-profile example is the 2023 Indian Premier League final. In that match, after Gujarat Titans scored 214/4 in 20 overs, rain interrupted play. When the match resumed, the DLS method was applied, reducing Chennai Super Kings’ (CSK) target. The target was revised from 215 runs from 20 overs to 171 runs from just 15 overs. CSK successfully chased this adjusted target, winning the final by 5 wickets via the DLS method. Furthermore, a 2018 IPL match saw the Kolkata Knight Riders lose to Kings XI Punjab, where KKR captain Dinesh Karthik expressed frustration that Kings XI Punjab suddenly needed “run-a-ball” after the DLS revised target (125 in 13 overs) was calculated following a rain delay.

Minimum Over Requirements for a Result

For a result to be declared using the DLS method in limited-overs formats, a minimum number of overs must have been bowled in the second innings.

The minimum over requirements are:

- One Day Internationals (ODIs): Each team must have faced at least 20 overs.

- Twenty20 (T20) Matches (including IPL): Each team must have faced at least five overs.

If conditions prevent a match from reaching this minimum length after an interruption, the match is declared a “no result”. The DLS Par Score is first calculated once Team 1’s innings has concluded. If the match is abandoned during the second innings, the team batting second must have reached or surpassed the D/L Par Score for a win, provided the minimum over threshold has been met.

Evolution from D/L to DLS (The Stern Update)

The DLS method is not static; it is the culmination of decades of statistical analysis and refinement, moving from the original Duckworth-Lewis method to the modern Duckworth-Lewis-Stern system to better adapt to shifting scoring patterns in the global game.

The Original Inventors: Duckworth and Lewis

The system was originally conceived by two English statisticians, Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis. They introduced the D/L method in 1997, responding to the need for a mathematically sound way to reset targets in interrupted matches, which became officially adopted by the ICC in 1999. Duckworth viewed the problem as a mathematical one requiring a mathematical solution. The D/L system relied on resource percentage tables, converting wickets and overs into a resource value. Initially, a single version, the Standard Edition, was used. Frank Duckworth passed away in 2024 at the age of 84.

Refining the Model for Modern T20 Scoring

As cricket evolved, particularly with the rise of high-scoring T20 matches, it became clear that the original D/L model needed adjustments. The original model was found to have an “inherent weakness” when dealing with very high first-innings scores (350+). The 2010 England versus West Indies World T20 match highlighted that D/L, while fair for ODIs, was still somewhat unsuited for T20s, resulting in a target that many experts felt was too low.

In 2013, the ICC appointed American-born, Australian-based data analytics professor Steven Stern to improve the system. Following his contribution, the system was renamed the Duckworth-Lewis-Stern (DLS) method in November 2014. Stern refined the model to better fit modern scoring trends, recognizing that teams chasing high totals need to maintain a higher scoring rate early on rather than focusing purely on preserving wickets. The updated DLS system universally alters the scoring calculations to produce more accurate revised targets, reflecting the aggressive nature of contemporary limited-overs cricket.

The Professional vs. Standard Editions

The DLS method is applied using two main versions: the Standard Edition and the Professional Edition.

- Standard Edition: This was the original version, which uses a single published reference table of resource percentages. It relies on the assumption that performance is proportional to the mean (average), regardless of the actual score. The Standard Edition is typically used at lower levels of the game where a computer is not guaranteed to be present. In the Standard Edition, if Team 2’s resources are greater than Team 1’s (R2 > R1), the target is increased by the expected average runs scored with that extra resource, using a benchmark figure called G50 (the average expected 50-over total).

- Professional Edition: Introduced around 2004, this version uses more sophisticated statistical modeling and is mandatory for all international cricket, including ICC tournaments and major leagues like the IPL. In the Professional Edition, the resource percentages vary depending on the first innings total, essentially creating a different table for every score. This version addresses the flaws seen in the Standard Edition when dealing with high scores, allowing the target to simply be increased proportionally (S × R2/R1) when R2 > R1. The actual resource values used in the Professional Edition are not publicly disclosed, necessitating the use of specialized computer software for calculations.

DLS Strategy and Betting Insights

For players, captains, and those interested in the dynamics of match outcomes (like betting enthusiasts who frequent VIPJEE), understanding DLS is crucial for in-game strategy, particularly during the second innings. The application of DLS transforms a standard run chase into a dynamic contest against a constantly changing mathematical target.

Importance of Staying Ahead of the Par Score

When an interruption is likely during the second innings, the chasing team’s primary strategic goal is to keep itself ahead of the DLS par score. Conversely, the bowling team (Team 1) aims to keep the chasing team (Team 2) behind the par score. The D/L par score is the total number of runs Team 2 would be expected to have scored at that moment to successfully match Team 1’s score. If the match is abandoned, the team ahead of the par score is declared the winner (provided minimum overs have been bowled). This par score is often shown on scoreboards and computer printouts and is updated after every ball.

The par score itself increases continuously with every ball bowled and every wicket lost, reflecting the increasing amount of resources used. A critical lesson, learned dramatically by South Africa in the 2003 World Cup, is that the par score displayed is the score required for a tie; the actual target required to win is one run more.

Wickets as the Heavily Weighted Resource

A frequent criticism of DLS relates to its weighting of resources: wickets are considered a much more heavily weighted resource than overs. In a situation where rain is imminent during a run chase, the DLS calculation often rewards the team batting second for preserving wickets, even if they are scoring at what might seem a “losing” rate. This suggests that a strategic approach when facing a large target with rain threatening might be to prioritize wicket preservation, even at the cost of slower scoring, to maximize the benefit of DLS in case of an interruption.

This priority—keeping wickets in hand—is consistent with traditional cricketing logic, but critics argue it can lead to perverse incentives, where slow scoring is rewarded under rain threat. The DLS Professional Edition, updated in 2015, attempted to address this by revising the required scoring rate for large targets, thereby encouraging faster scoring early in the second innings.

Comparing DLS Accuracy with Machine Learning Predictions

While DLS is the official standard, statistical analysis suggests its accuracy is finite. Studies comparing DLS accuracy in predicting match outcomes against machine learning (ML) algorithms show that the ML classifiers often perform better. For instance, one study found that the overall D/L formula accuracy was 78.12% when applied to 63,000 overs samples, rising to 83.74% when excluding the first 20 overs (where DLS is not applicable for a result).

ML algorithms, like Neural Networks, showed slightly better accuracy in predicting match winners at various stages. Furthermore, ML classifiers showed a “big leap in prediction accuracy… at 10 overs during second innings,” predicting the result with comparable accuracy to what DLS achieves after 20 overs, which is highly relevant for betting predictions during the early phase of the game. This suggests that DLS can be viewed as an attribute in a predictive model, but it is not the ultimate predictor of the match outcome.

The Domestic Alternative: VJD Method in India

While DLS is used internationally and in the IPL, India has its own method—the V. Jayadevan (VJD) method—which is successfully applied in many domestic tournaments and is often championed by local experts. This comparison is highly relevant in the context of Indian cricket, particularly the IPL, where there have been calls to adopt the domestic system.

VJD’s Dynamic Curves and Scoring Phases

The VJD method was developed by Indian engineer V. Jayadevan and is currently used in BCCI domestic tournaments, such as the Vijay Hazare Trophy and the Syed Mushtaq Ali Trophy. Unlike DLS, which relies heavily on resource percentages, VJD utilizes two dynamic scoring curves: one for the normal scoring pattern and one for the accelerated phase.

The VJD method assumes a specific structure to the limited-overs innings:

- Powerplay: A phase of initial acceleration.

- Middle Overs: A phase of stabilization.

- Slog Overs: A phase of rapid scoring.

By providing different weightage for runs scored during these distinct stages, VJD is considered by many experts to be closer to real match scenarios and more flexible in capturing modern run-rate trends compared to DLS.

Why BCCI Uses VJD for Domestic Tournaments

Despite the ICC’s preference for DLS, the BCCI maintains the use of the VJD method for its domestic competitions. This sustained domestic use demonstrates strong faith in VJD’s accuracy and fairness within the Indian cricketing context.

Kolkata Knight Riders captain Dinesh Karthik once questioned the use of DLS in the IPL, suggesting that since the IPL is an Indian domestic tournament, the proven Indian method (VJD) should be considered for future use. The adoption of VJD is supported by experts like Sunil Gavaskar and the inventor V. Jayadevan himself, who notes that VJD provides “smoother, more realistic targets” without the sudden jumps sometimes seen in DLS, especially during high scores.

Accuracy Differences in High-Scoring Games

One of the most significant differences between DLS and VJD lies in their performance when calculating targets for high-scoring matches, which are now commonplace in T20 and ODI cricket. Critics argue that DLS can be “sluggish” in high totals, sometimes underestimating or overestimating targets, and may unfairly benefit the chasing team if early overs are lost.

VJD, by dividing the innings into distinct scoring phases, appears to adapt better to modern scoring rates and provides a more balanced calculation for totals exceeding 300 in ODIs or 200 in T20s.

The following table illustrates the comparison of revised targets set by both methods for a 50-over match reduced to 20 overs for the chasing team:

| Scenario | Team 1 Score (50 overs) | DLS Target (20 overs) | VJD Target (20 overs) |

| Low Score | 200 | 124 | 118 |

| Average Score | 250 | 154 | 142 |

| High Score 1 | 300 | 163 | 163 |

| High Score 2 | 350 | 174 | 182 |

Observation: For very high totals (e.g., 350 runs), the DLS target shows a smaller increase (174) compared to the VJD target (182), indicating that VJD maintains a smoother, more consistent rise that reflects the expected aggressive scoring rate needed to chase such a target in a shortened game.

While the ICC maintains DLS due to global familiarity, standardization, and administrative continuity, the VJD method is recognized as offering better flexibility and realism for high-scoring modern formats, fueling the ongoing debate about the best approach for rain-affected match results.

Conclusion: The DLS Method in the IPL

The Duckworth-Lewis-Stern (DLS) method is far more than a simple rain rule; it is a complex, data-driven system, refined over decades that ensures fairness in limited-overs cricket, including the high-stakes environment of the IPL. Adopted by the IPL through the mandate of the ICC Playing Conditions, DLS relies on the concept of maximizing or minimizing the resources available (wickets and overs) to determine a statistically equivalent target score.

While the system has faced criticism for its complexity and its historic emphasis on wicket preservation, the updates made by Steven Stern have attempted to keep the model relevant amidst the explosive scoring of the T20 era. For platforms like VIPJEE, the DLS par score acts as a vital metric for tracking potential match outcomes, especially when viewed alongside advanced predictive models. Although India utilizes the VJD method domestically, reflecting a valid and potentially more accurate approach for high-scoring games, DLS remains the essential, globally standardized method that dictates results and betting outcomes in the Indian Premier League.