TLDR

LBW stands for Leg Before Wicket, one of the most debated and complex ways a batter can be dismissed in cricket. In simple terms, a player can be ruled out LBW if the ball would have gone on to hit the stumps, but was stopped by the batter’s body instead (usually the pad or leg).

But there’s more to it than that. The umpire has to check four key things:

- Was the delivery legal (not a “no ball”)?

- Did the ball hit the body before the bat?

- Did the impact happen in line with the wickets?

- Would the ball have hit the stumps?

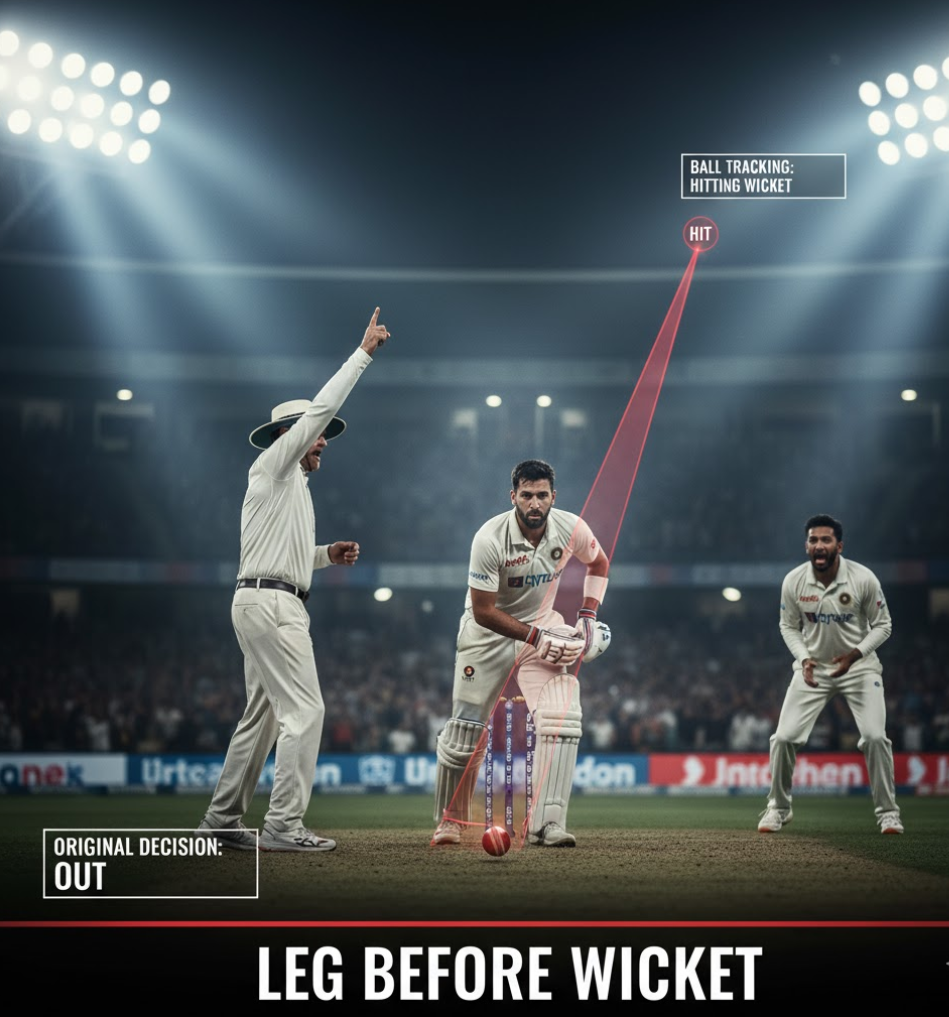

At the professional level, the Decision Review System (DRS) and its ball-tracking technology now play a huge role in these calls, adding precision, reducing controversy, yet still leaving room for the “Umpire’s Call” in close cases. If you love understanding the finer details of cricket (or even want to sharpen your cricket betting insights), this one’s worth unpacking properly.

So, What Exactly Is “Leg Before Wicket”?

LBW, or Leg Before Wicket, as defined in Law 36 of the Laws of Cricket, exists to stop batters from using their pads or bodies as shields. Imagine if players could just block every ball with their legs; bowling someone out would become nearly impossible! The rule keeps things fair, making sure skill, not obstruction, decides the contest between bat and ball.

The Full Form of LBW and What It Really Means

If you’ve ever wondered, what does LBW stand for? It’s literally Leg Before Wicket, describing when a batter’s body (usually their leg) ends up in front of the stumps, cutting off the ball’s path. Despite the name, it’s not just about the leg. Any part of the body (except the hands holding the bat) can cause an LBW, even the head, though that’s obviously a rare and unlucky way to get out. The key idea: the ball must hit something that’s part of the striker’s clothing or protective gear, not the bat or the bat-holding hand.

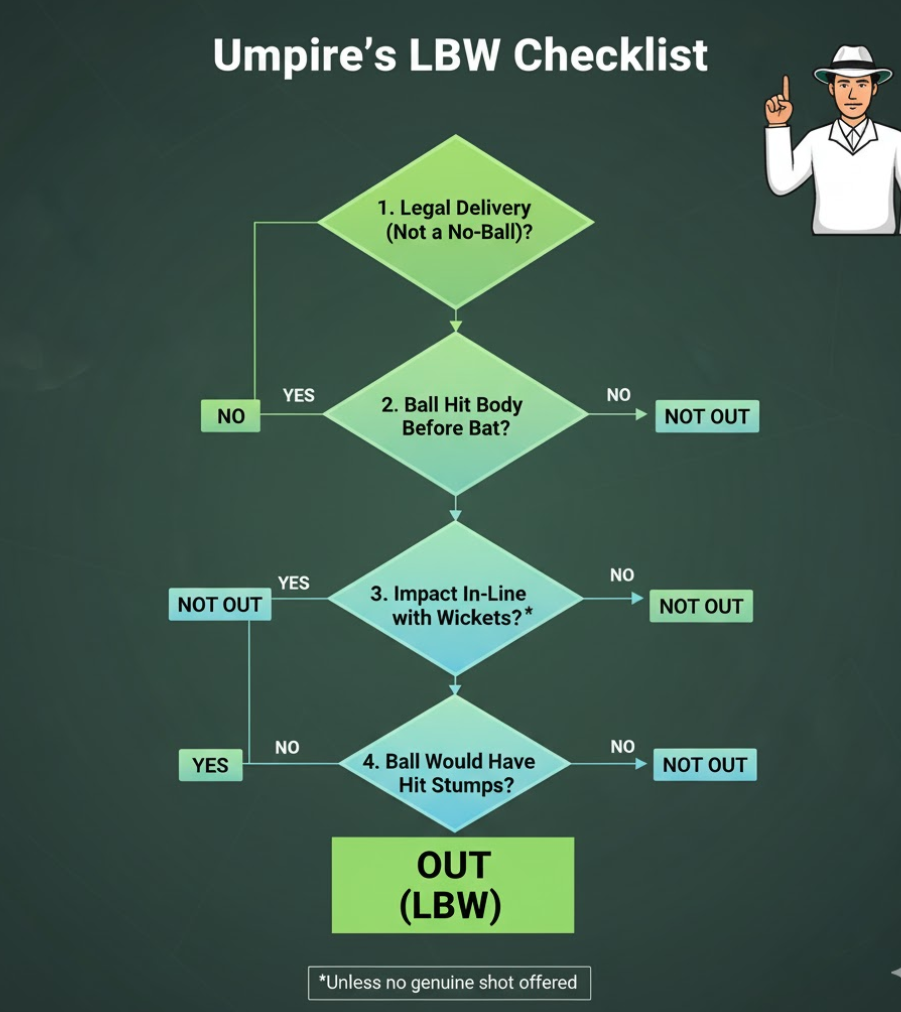

The Four Pillars of the Umpire’s Decision

Every LBW decision starts the same way, with the fielding side’s classic shout: “Howzat?!” From there, the umpire runs through four mental checkpoints before raising that finger:

- Was it a legal delivery?

No “no balls” allowed here. If the bowler oversteps the popping crease, lands their back foot outside the return line, or sends a full toss above the batter’s waist without pitching, the delivery’s illegal, and LBW is immediately off the table. - Did it hit the body first, not the bat?

If the ball hits the bat, or the hand holding the bat before striking the body, the LBW appeal is dead. - Was the impact in line with the stumps?

The ball must strike the batter between wicket and wicket, unless they didn’t offer a shot at all (we’ll get to that next). - Would it have hit the wickets?

This is the heart of the decision. The umpire has to be convinced that the ball’s natural path would have led it to hit the stumps, even if it might have bounced again before doing so.

Only if all four answers are “yes” can the batter be ruled out LBW.

The Role of the Bat and Intent

Here’s where things get spicy. Whether the batter tried to play a shot or not changes everything.

- If the batter attempts a genuine shot, they get a safety net: even if the ball would’ve hit the stumps, they can’t be given out if it struck them outside the line of the off stump.

- But if they don’t play a shot, choosing instead to “pad it away”, that protection disappears. Even if the impact is outside off stump, they can still be out, as long as the umpire believes the ball would’ve hit the wicket.

This part of the law was added back in the 1970s to curb the dull tactic known as pad play, when defensive batters would simply block balls with their pads, safe in the knowledge they couldn’t be out LBW. It worked, too. Today, players have to use their bats, not just their bodies.

Technology Steps In: DRS and “Umpire’s Call”

Fast forward to modern cricket, and technology has changed everything. Systems like Hawk-Eye and ball tracking help simulate where the ball would have gone after impact, giving both players and fans a clearer look at tight LBW calls. Still, cricket keeps a human touch: the “Umpire’s Call” rule means that if the prediction is too close to call, the original on-field decision stands. It’s a neat balance- science sharpens accuracy, but respect for the umpire remains.

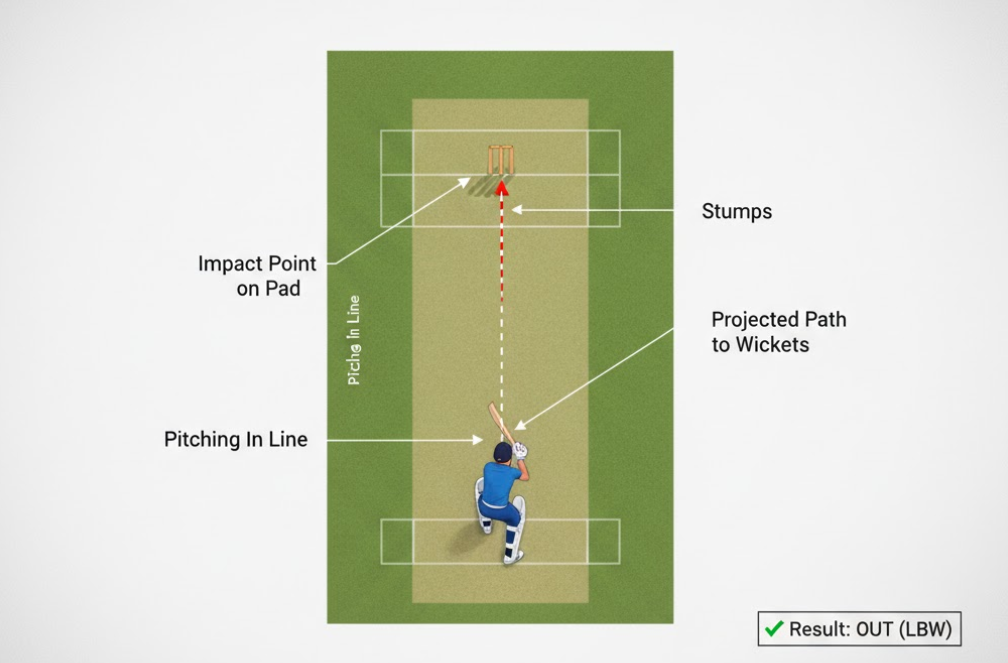

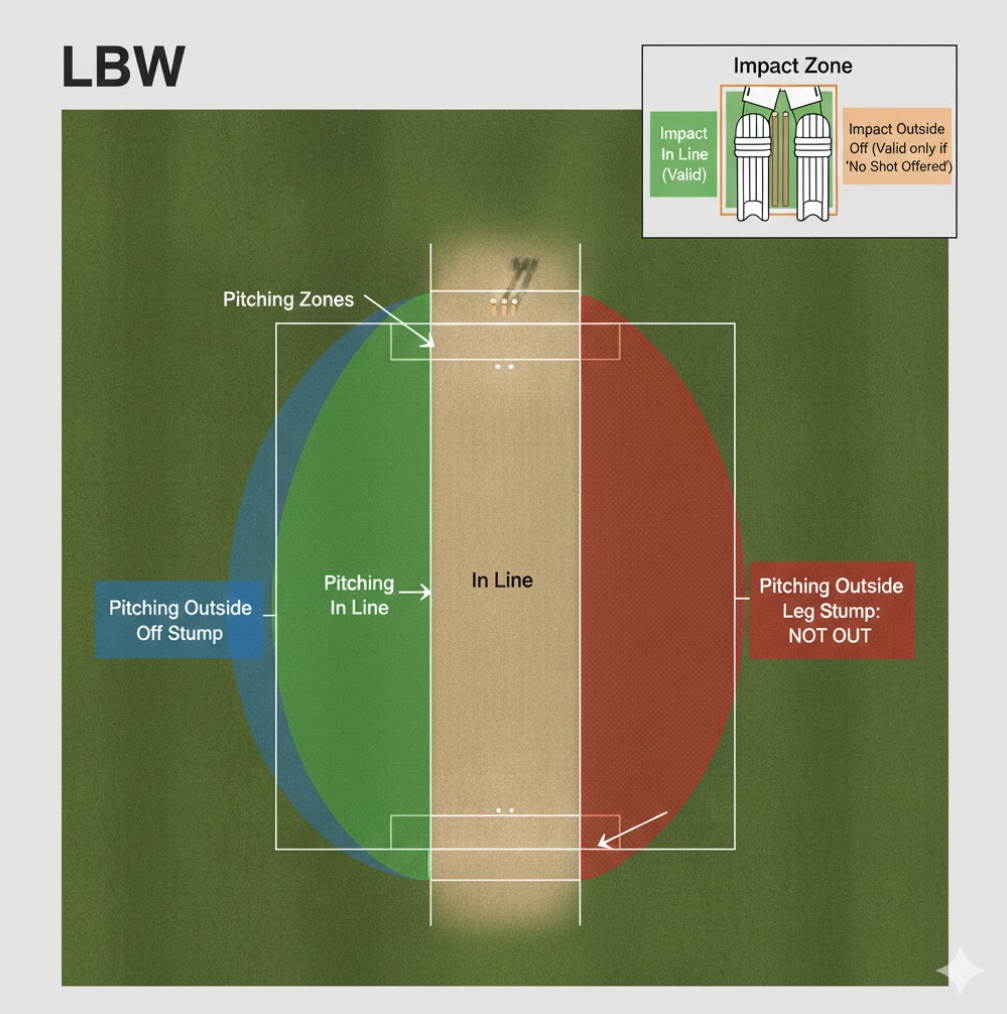

Pitching and Impact: Decoding the Crucial Zones

To really understand what LBW means in cricket, you’ve got to dig into the three zones that decide everything, the Pitching Zone, the Impact Zone, and the Wicket Zone (the ball’s predicted trajectory). This is where the umpire’s decision gets technical. Where the ball lands, where it hits the batter, and where it was heading, and these aren’t random details. They’re part of a framework that’s been fine-tuned over centuries to keep the contest between bat and ball fair, thrilling, and just a little bit controversial.

Pitching Zone Restrictions: The Leg Stump Boundary

Let’s start with where the ball lands– the Pitching Zone. There’s one absolute rule here: If the ball pitches outside the line of the leg stump, the batter cannot be given out LBW.

No debates. No “umpire’s call.” It’s black and white.

Why? Because cricket needs balance. Without this leg-side restriction, bowlers could spend all day aiming down the leg, trapping batters with suffocating lines and packed leg-side fields. It’d kill the game’s rhythm, no flair, no shot-making, no entertainment.

So, this simple boundary: the line of the leg stump is cricket’s way of saying “Play fair, attack the stumps.” It forces bowlers to aim for more aggressive, wicket-to-wicket deliveries rather than just choking the batter’s scoring options.

A legitimate LBW can only come from a ball that pitches either:

- In line with the stumps (between off stump and leg stump), or

- Outside the off stump (where swing and spin can bring the ball back in).

Anything that lands outside leg stump? Appeal over. Doesn’t matter if it would’ve shattered all three stumps, it’s simply not out.

The Impact Point: In Line vs. Outside Off Stump

Now, let’s move to the moment of truth, the Impact Zone, where the ball actually hits the pad (or body).

This spot matters enormously, especially when the batter plays a shot. If they’re attempting a genuine stroke, the impact must be in line between wicket and wicket. If the ball strikes them outside the off stump, the appeal is dismissed even if ball-tracking later shows it would have gone on to hit middle stump.

That rule exists for a reason: if a player is trying to play a legitimate shot outside off, you can’t assume they were padding on purpose. Sometimes, batters just misjudge the line or get squared up while trying to avoid an edge to the keeper or slips. The laws protect that intent.

The Critical Exception: When No Shot is Offered

Here’s where things flip completely.

If the batter does not attempt a genuine shot, the “impact line” protection vanishes. The umpire can now rule the player out LBW even if the ball hits them outside the line of off stump, provided it was straight enough to hit the wicket.

This “no shot offered” clause was added in the 1970s and it changed cricket forever. Before then, defensive players could just stick their pads out at balls pitched outside off stump, completely safe from LBW. It was called pad play, a tactic that frustrated bowlers and bored spectators to tears.

So, lawmakers said enough was enough. The new rule rewarded intent, encouraging batters to play proper shots and punishing those who chose pure defence. It made cricket more attacking, fairer, and frankly, more watchable.

In short: if you don’t offer a stroke and the ball’s hitting the stumps, you’re gone, even if it clipped you outside off.

| LBW Decision Factor | Condition for OUT (General Rule) | Condition for OUT (No Shot Offered) |

| No Ball | Must not be a No Ball | Must not be a No Ball |

| Bat Contact | Must not hit bat first | Must not hit bat first |

| Pitching Zone | Must pitch in line or outside off stump | Must pitch in line or outside off stump |

| Impact Zone | Must be in line with the wickets | Can be outside the off stump |

| Trajectory | Must be predicted to hit the wickets | Must be predicted to hit the wickets |

A History of Controversy: Why LBW Rules Evolved

The LBW rule has always been one of cricket’s great conversation starters, as tricky to grasp for newcomers as football’s offside law. And like any good drama, it’s evolved through decades of tweaks, arguments, and reform.

Origins of the Law (1774) and Preventing Pad-Play

The earliest written Laws of Cricket (1744) didn’t even mention LBW. Back then, bats were curved, and players stood side-on, far from blocking the stumps. But as bats became straighter, clever players started using their legs to stop the ball, making it nearly impossible for bowlers to get them out. Something had to change.

So, in 1774, the first version of the LBW rule appeared. It stated that a batsman was out if they deliberately stopped the ball from hitting the wicket with their leg. The problem? It required the umpire to read the player’s intention, which was almost impossible.

That “intention” clause was quickly scrapped. By 1839, the MCC had refined the law: a batter was out LBW if the ball pitched between the wickets and would have hit the stumps. That version lasted nearly a hundred years- simple, functional, and fair enough for its time.

The Major Shift in 1935: Pitching Outside Off Allowed

By the early 1900s, cricket was changing. Batting was becoming dominant, and defensive “pad-play” was creeping back. Players like Arthur Shrewsbury turned their pads into secondary bats, deflecting balls they didn’t want to play. Fans and purists hated it- matches dragged, bowlers grew frustrated, and entertainment dipped.

So in 1935, a radical experiment began: batters could now be dismissed LBW even if the ball pitched outside the line of off stump, as long as it struck them in line with the stumps and would’ve hit them. That tweak opened up new possibilities for bowlers. Suddenly, swing and spin deliveries that started wide but curved in, the stuff of beauty, could now actually get results. It also discouraged extreme defensive play.

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack later praised the move, calling it a change that brought more “enterprising cricket” and fewer dull draws. It did, however, tilt the scales slightly toward inswingers and off-spinners, something later critics noted. Still, it restored balance and revived excitement.

1970s: The “No Shot Offered” Revolution

Even after the 1935 fix, one problem lingered: defensive players were still exploiting the rule by padding away deliveries pitched outside off stump. It was especially rampant through the 1950s and 1960s, when slower pitches encouraged survival over strokeplay.

Enter the 1970s reform, first tested in 1972, then formally added to the Laws in 1980.

The rule stated:

- If no genuine shot is offered, the batter can be out LBW even if struck outside the off stump.

That one sentence changed batting psychology forever. Now, every delivery demanded intent. Players could no longer hide behind their pads- they had to play cricket, not block it. This shift encouraged attacking cricket, rewarded skill, and made bowlers feel like they had a fighting chance again. It was one of those rare law changes that improved both fairness and entertainment in equal measure.

| LBW Law Evolution Milestone | Key Change | Effect on Dismissal Criteria |

| 1774 (Origin) | Batter out if he “deliberately stopped the ball from hitting the wicket with his leg.” | Required intent (later removed) and leg interference. |

| 1839 (Standard) | Ball must pitch in line with wickets and hit in line. | Set the standard that pitching must be between the wickets. |

| 1935 (Pitching Expanded) | Batter can be out if ball pitches outside off stump, but still hits in line. | Countered batsmen padding away outside-off deliveries. |

| 1972 (No Shot Offered) | If no shot is offered, impact point outside off is irrelevant. | Directly penalized overly defensive ‘pad play’ outside off. |

The Decision Review System (DRS) and Umpire’s Call

If LBW decisions used to spark heated debates, then the Decision Review System (DRS) turned those debates into data-driven drama. Cricket’s gone from pure human judgment to a beautiful hybrid, a dance between technology and tradition.

For cricket lovers and especially betting enthusiasts on VIPJEE, understanding how DRS and the infamous “Umpire’s Call” work isn’t just trivia, it’s strategy. One marginal decision can flip a match, a series, or a wager.

Technology in Play: Ball Tracking and Accuracy

DRS gives players the right to challenge the on-field umpire’s call, and nowhere is it more powerful than in LBW decisions. At its heart is ball tracking technology, like Hawk-Eye, which uses high-speed cameras to map the ball’s journey in 3D, from the bowler’s hand to its impact point, then projecting where it would have gone had the batter not been there.

This predictive modeling has changed everything.

Analyses show that balls striking an outstretched pad often go on to hit the stumps far more often than old-school umpires believed. It’s proof that technology has sharpened the game’s fairness and accuracy.

Even Dave Richardson, former ICC General Manager, once noted that DRS helped umpires become less conservative, more willing to give batters out knowing the system could correct them. Today, LBW accuracy exceeds 95% in international matches, an incredible leap from the pre-tech era.

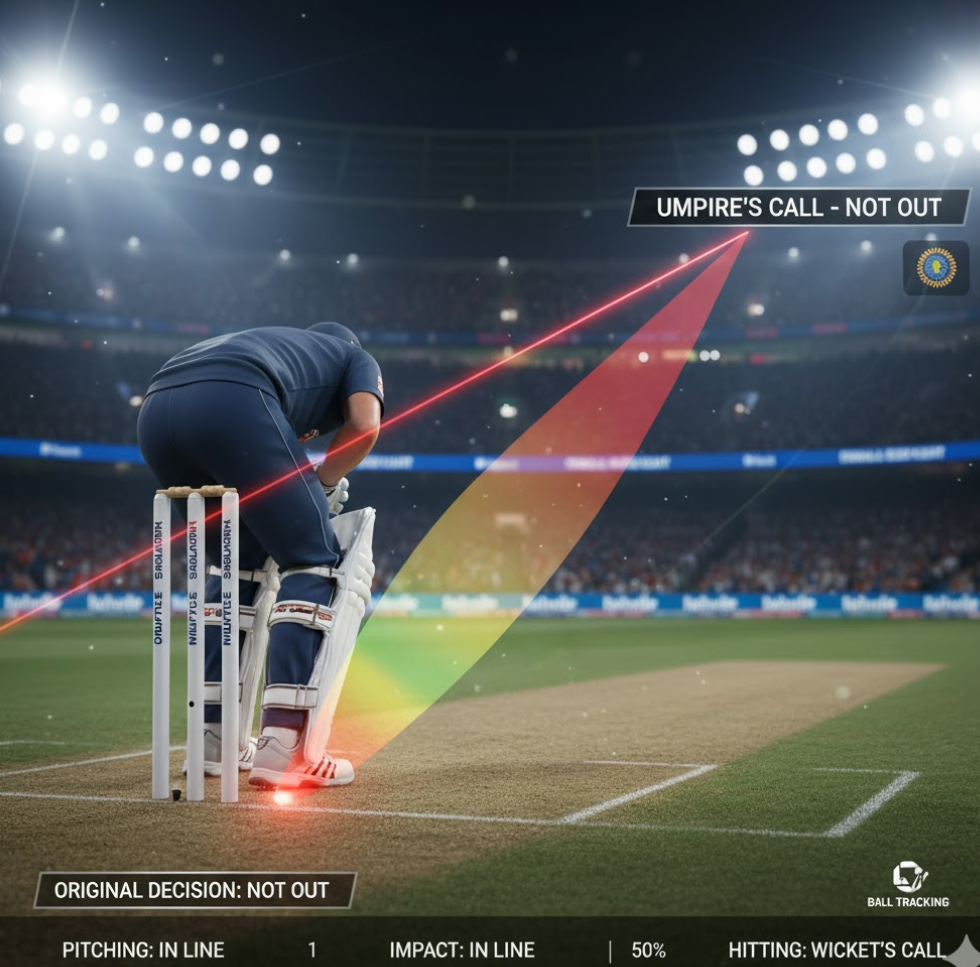

Understanding the Umpire’s Call Margin

Now, here’s where art meets science. Even with DRS, cricket keeps one foot planted in tradition through the Umpire’s Call, a safeguard designed to preserve both human authority and the spirit of doubt that makes the sport human.

Umpire’s Call comes into play when the ball-tracking data produces a marginal outcome, especially in the Impact Zone (where the ball hits the pad) or the Wicket Zone (where it’s projected to hit the stumps).

Remember, DRS isn’t meant to hunt perfection, it’s there to correct clear errors. Every prediction still carries an element of uncertainty, and the Umpire’s Call acknowledges that.

Here’s how it works:

- Wicket Zone (Hitting the Stumps):

If the original call was “Not Out,” DRS requires that more than 50% of the ball must be shown hitting the stumps for the decision to flip to “Out.”

If only part of the ball clips the stumps (less than 50%), it’s deemed Umpire’s Call, and the “Not Out” stands. - Impact Zone:

Determining where a fast-moving ball meets a moving pad isn’t pinpoint exact, so this zone, too, can fall under Umpire’s Call. - Pitching Zone:

This one’s absolute. No grey area here, if the ball pitched outside leg stump, it’s never out. No appeal to science will change that.

And here’s a crucial point for teams (and bettors tracking review stats):

If a review ends with Umpire’s Call, the on-field decision remains, but the team does not lose their review. In most formats, each side gets two unsuccessful reviews per innings, so smart timing is everything.

| Scenario | Original Decision | DRS Prediction | Final Outcome | Review Count Impact |

| Clear Error | Out | Ball missing stumps entirely | Overturned to Not Out | Review successful, retained |

| Clear Error | Not Out | Ball entirely hitting stumps | Overturned to Out | Review successful, retained |

| Marginal | Out | Less than 50% of ball hitting stumps | Umpire’s Call (Out stands) | Review lost |

| Marginal | Not Out | Less than 50% of ball hitting stumps | Umpire’s Call (Not Out stands) | Review retained |

DRS Statistics and Controversial Moments

LBW decisions are the most frequently reviewed dismissal type in international cricket, accounting for 74% of all referrals. However, only 22% of these LBW referrals are ultimately successful in overturning the original decision.

The introduction of DRS has led to ongoing debate about its application:

- The Debate on Umpire’s Call: Some prominent figures argue that if the ball is hitting the stumps, even marginally, it should be ruled out, advocating for removing Umpire’s Call entirely. They feel that if technology is used, it should take precedence over subjectivity. Others maintain that Umpire’s Call is essential, as it accounts for the margin of error in technology and preserves the umpire’s role, preventing the game from becoming overly technical or resulting in two-day Test matches due to excessive dismissals.

- Iconic Controversies: The LBW rule has played a central role in highly controversial matches, often affecting the momentum and results of major tournaments. A prime example is the 2011 Cricket World Cup semi-final, where Sachin Tendulkar was given out LBW by the on-field umpire, but the decision was overturned on DRS, which projected the ball missing the leg stump. This moment fueled intense debate regarding the technology’s accuracy and integrity, especially considering Tendulkar went on to score a match-winning 85 runs.

Strategic Implications for Batting, Bowling, and Betting

Given the complexity and technical margins associated with the question, what does the term LBW stand for in cricket, the rule has profound implications for game strategy, influencing everything from a batsman’s stance to a bowler’s line, and, crucially for VIPJEE’s audience, the dynamic probabilities in cricket betting.

Tactics to Avoid Being Adjudged Leg Before Wicket

For batsmen, avoiding LBW involves superior technique, particularly focusing on footwork and positioning.

- Footwork and Positioning: Moving the feet early is key. A batsman can employ a front foot defense to step forward and meet the ball early, improving their ability to judge the line and align with the stumps. Quick back-foot movement is necessary to adjust to various lengths.

- Playing the Shot: As established by the 1970s rule change, playing a genuine shot provides significant protection. If the ball pitches outside off stump, playing a shot means the batter cannot be given out LBW even if the ball hits them outside the off stump. This encourages batsmen to play attacking shots, disrupting the bowler’s rhythm and reducing LBW risks.

- The Off-Stump Guard: Some modern batsmen utilize tactics like taking guard far outside the off stump, or positioning their front foot wide, to intentionally place the impact point outside the off-stump line. This is done in the hope that if the ball does swing or spin sharply into the wickets, the impact will be ruled outside the protected zone (if a shot is offered). This approach, while effective against sharp inward movement, can be criticized as being negative play.

- Leaving the Ball: While leaving balls that are clearly not heading toward the stumps is wise, leaving a ball that is aimed close to the off-stump line, especially from a spinner, increases the risk of being out LBW if the impact is in line. If a batsman lifts the bat high to avoid playing a delivery (“Shoulder Arms”), they are highly vulnerable if the ball hits their body in line, especially if they are far down the pitch.

Bowlers’ Strategy: Line, Length, and Variation

LBW is a primary mode of dismissal, making it a key tactical target for bowlers, especially spinners and those generating inward swing (inswingers) or seam movement (nipbackers).

- Line and Length: The most effective bowling strategy to generate LBW opportunities is line and length bowling. This involves pitching the ball on a “good length” and just outside the off stump. This line, often called the “corridor of uncertainty” or “fourth stump line,” forces the batsman to play a shot because the ball threatens to hit the stumps. An LBW dismissal often punishes a batter who is indecisive, neither playing a committed shot nor making a decisive leave.

- Inward Movement: Bowlers who generate significant in-swing or off-spin (which turns into the right-handed batter) have a natural advantage for LBW appeals, provided they maintain an attacking line. Fast bowlers can target the batter’s toes with a toe-crusher (a yorker bowled with inswing) aimed at the block hole, which is extremely difficult to defend.

- Round the Wicket: Bowling from around the wicket can effectively disrupt a batsman’s rhythm, particularly for fast bowlers targeting the pads, or off-spinners creating an angle into the right-hander. However, the risk remains that if the bowler attacks the pads too aggressively outside leg stump, the ball might be ruled as pitching outside leg, which cancels the LBW appeal immediately.

LBW Decisions and Their Impact on Cricket Betting

LBW decisions are high-stakes moments that can drastically alter the course of an innings or a match

- Probability and Match Momentum: The probability of a wicket falling LBW is influenced by the pitch conditions and the bowling style. Pitches that assist swing and turn tend to increase the proportion of LBW dismissals. When a bowler who specializes in inward movement (like an inswing bowler or off-spinner) is operating, the possibility of an LBW rises, affecting the live odds for the next dismissal method.

- Review Strategy and Utilization: Since each team has a limited number of reviews (e.g., two unsuccessful reviews per innings in the 2023 ODI World Cup), the decision to use a DRS referral is a strategic high-risk/high-reward gamble. Teams must quickly “Check the basics” such as pitching outside leg and evaluating the impact point before appealing. A poor decision to review a marginal LBW call can leave the team vulnerable later in the innings when a clearer error needs overturning. This tactical element adds a layer of uncertainty that betting markets must account for.

- Umpire’s Call Implications: The Umpire’s Call rule adds a margin of error that favors the on-field umpire’s initial decision. For betting, this means that close decisions are less likely to be overturned than clear mistakes. When betting on whether a review will be successful or the next dismissal type, analysts must weigh the likelihood of the decision falling within that marginal grey area. As some studies have suggested historical biases or leniency toward home captains or specific national players in the past, analyzing officiating trends and perceived biases can become an esoteric layer of betting analysis, even if the intention of neutral umpires and DRS is to remove such subjectivity.

Conclusion

So, after all this, what does LBW really stand for? Sure, it’s Leg Before Wicket, but it’s also Logic Before Whimsy, the rule that keeps cricket both fair and thrilling. From its 1774 origins aimed at stopping cheeky pad-play to today’s ultra-precise DRS era, LBW has evolved into one of sport’s most fascinating judgment calls.

Technology has lifted umpiring accuracy to over 95%, yet the soul of the game remains, that heartbeat of uncertainty in every “Howzat!” And for fans, players, and bettors alike, mastering LBW means understanding cricket’s truest balance: human instinct meeting technological precision. It’s the rule that defines cricket- complex, beautiful, and still stirring debate centuries later.

FAQs

Q1: Can a batsman be out LBW if the ball pitches outside the leg stump?

No, if the ball pitches outside the line of the leg stump, the batter cannot be given out LBW. This rule is firmly in place, even if the ball would have clearly gone on to hit the wickets. This exclusion was introduced historically to discourage negative bowling tactics that involve aiming consistently down the leg side, frustrating the batsman and leading to overly defensive play.

Q2: Why is the point of impact crucial in LBW decisions?

The point of impact (where the ball hits the body/pad) is critical, particularly if the batsman offers a shot. If a genuine shot is played, the ball must hit the batsman’s body in line with the wickets (between wicket and wicket). If the impact occurs outside the off stump while playing a shot, the batter is not out. This rule aims to protect the batsman when they are actively trying to hit the ball, assuming the interception outside off stump was accidental, not intentionally obstructive.

Q3: How does the “No Shot Offered” rule change the LBW decision criteria?

If a batsman makes no genuine attempt to play the ball, the normal rule requiring the impact to be “in line” is waived. In this specific case, the batsman can be given out LBW even if the ball strikes them outside the line of the off stump, provided the umpire is certain the ball would have hit the wickets. This modification was introduced in the 1970s to penalize overly defensive ‘pad play’ outside the off stump.

Q4: What does the term LBW stand for in cricket and when was it introduced?

What does the term LBW stand for in cricket? The term is an abbreviation for Leg before Wicket. The LBW rule was first introduced into the Laws of Cricket in 1774, primarily because batsmen had begun using their legs to prevent the increasingly straighter deliveries from hitting the stumps.

Q5: What is the significance of “Umpire’s Call” under DRS for LBW?

Umpire’s Call applies when the ball-tracking technology indicates a marginal outcome, typically if the predicted path shows the ball only clipping the stumps (less than 50% of the ball hitting) or if the impact point determination is marginal. In such ambiguous situations, the original decision made by the on-field umpire stands, ensuring the umpire’s authority is maintained despite the technology. Crucially, if the review results in Umpire’s Call, the team retains the review.